Brunelleschi's Cupola

Excusez nous mais cette page n'est pas été encore traduite en Français

The construction of the cupola of the Cathedral was one of the most imposing tasks of the Renaissance, it kept the Florentines engaged in debates and competitions for years but, once it was completed, thanks to the genius of Filippo Brunelleschi, it became the symbol of the city itself and the new, revolutionary Renaissance architecture. Arnolfo's project for Santa Maria del Fiore, which became even more imposing with Francesco Talenti's modifications, had left the basilica with an enormous problem, that of closing the chancel with a roof. Arnolfo's project certainly included a cupola, but a low one, similar to some of the Byzantine-type spherical coverings that can still be seen today in southern Italy: a virtual portrayal of it is shown in the fresco in the Spanish Chapel in Santa Maria Novella, carried out in 1365-67, where the Cathedral is shown with a strange cupola which never actually existed. In the end, the cathedral was so enormous that the usual methods of fixed scaffolding from the ground could not be used. After all, it seemed quite impossible to roof over a space of 45,5 metres in diameter without some sort of reinforcement.

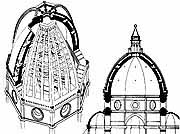

Axonometric drawing and section of the Cupola

The challenge was resolved by Brunelleschi,

expert in the rules of perspective and mathematics, as well as being a real

enthusiast for the construction techniques used by the ancient Romans. He

got his final inspiration from an attentive study of the cupola of the Pantheon,

which had also been carried out without scaffolding and with a double wall.

When he returned to Florence, the artist suggested that a drum be built

above the chancel and then, when this structure was complete (in actual

fact making it even more complicated to construct the cupola), he returned

to Rome, chased by desperate messages from the Opera del Duomo. Eventually

he suggested announcing a competition for the project of a cupola with the

following requisites: it had to be octagonal, measure 46 metres in diameter

at the base, be built without scaffolding and appear to be at least double

in size: he was quite sure that he would win.

The drum of the

Cupola without marble

The competition was held in 1418 and Brunelleschi won it outright, but the directors of the Opera del Duomo stipulated that Lorenzo Ghiberti (who had already managed to snatch the commission from him for the north door of the Baptistery) should collaborate as overseer for the work. The artist was so offended that he nearly destroyed his model (the same one that we can see today in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo); his friends Donatello and Luca della Robbia instead advised him to pretend he was ill and leave all the responsibility to Ghiberti. He followed their advice and Ghiberti soon came to a standstill and had to admit that he was incapable of understanding the project and going ahead with the work.

Side view of the Cathedral

Having won a victory over his rival, Brunelleschi started the construction

in 1420 and spent the rest of his life working on it, although in the meantime

he did design other monuments that were to be a basic part of the profile

of Renaissance Florence. The final structure that he elaborated and completed

consisted in a double cupola of brick, laid herring-bone fashion, 91 metres

high, completely self-supporting and based on an unusual system of flying

rather than fixed centerings (which would of course have been impossible

because of the size). The exterior of the cupola, with domical vaults and

stone ribs at the corners, appeared much larger and "blown up" than

the interior, however it reproduced the same pointed arch profile to perfection.

The Lantern on top of the Cupola

The "Cupolone" or great cupola (as the Florentines have called it ever since) was completed in 1434. Two years later the lantern was placed in position (taking it from 91 to 114,5 metres in total height), while the four tribunes occupying the spaces created by the projections in the octagon of the apse were carried out in 1438. The decorations in the lantern were finished by 1446, when the great architect was on his deathbed. The finishing touches included the application of the decorations in the lantern (1461) and the positioning of the great copper sphere on the top (1474). Cast in Verrocchio's workshop and raised up thanks to a machine that was built with the help of Leonardo da Vinci, the ball fell off after being struck by lightning on July 17th 1600 and was replaced two years later by a larger one. A marble plaque commemorating the event is still visible on the paving in the square behind the Cathedral.

Baccio d'Agnolo's

unfinished balustrade

The decoration of the gallery around the drum was never finished: the balustrade designed by Baccio d'Agnolo and carried out on only one side of the octagon, did not meet with the approval of Michelangelo who, defining it "a cage for crickets", decreed its final condemnation. Brunelleschi's model was later to be copied by Michelangelo for the cupola of St. Peter's in Rome. Tourists will find the visit to the cupola really spectacular: although the climb up is somewhat tiring (463 steps), it is extremely interesting for understanding the method the architect used to build it while also giving a wonderful view over the city. It is also possible to stop in the interior of the dome on the way up to see the frescoes of the Last Judgement by Giorgio Vasari and Federico Zucchari from closer at hand.